Earlier this week Tom Bennett published an article in Guardian Education, called ‘Play is essential, but it takes work for children to succeed in the real world‘. In this article, Tom made the case that ‘learning through play’ is a “powerful vehicle for “folk” learning – the basic components of understanding reality. But is not so great once you want to do anything beyond that.” His argument makes four points. First, you need a teacher to learn anything beyond self-discovery. Second, learning requires hard work. Third, learning is often unpleasant. Fourth, there is a danger of learning through play becoming trivial.

Now, Tom is an engaging writer, he’s funny, erudite, and great with words. In fact he is sometimes so funny and so clever there is a danger of being swept along by the wonder of his prose and forgetting to actually look at what he is saying. Take this example, “When play becomes the vehicle of learning, the danger is you forget the wheels and focus on the fluffy dice.” Who could fail to love the argument of someone who writes so wittily? Yet, none of what Tom says in this article actually invalidates play as a medium for learning.

Let’s look at each of his points in turn.

First, ‘you need a teacher to learn anything beyond self-discovery’. Fine, but then there is nothing to stop an adult (even an expert, knowledgeable one) being involved in play. In fact, visit a classroom where play is used as a medium of learning and you will find teachers and students playing together, collaboratively. The adult will be guiding, facilitating, and mediating the learning, challenging the students, asking questions, and introducing new knowledge and skills. Nothing in learning through play means children have to play on their own.

First, ‘you need a teacher to learn anything beyond self-discovery’. Fine, but then there is nothing to stop an adult (even an expert, knowledgeable one) being involved in play. In fact, visit a classroom where play is used as a medium of learning and you will find teachers and students playing together, collaboratively. The adult will be guiding, facilitating, and mediating the learning, challenging the students, asking questions, and introducing new knowledge and skills. Nothing in learning through play means children have to play on their own.

Second, ‘learning requires hard work’. Again, fine, but then so does serious play (just watch Norwich City labouring away on a Saturday afternoon). Tom seems to dichotomise work and play, but work can often involve elements of play, and play can often involve elements of work. In fact, play without challenge and without tension is rarely interesting and children will quickly lose interest. It is quite possible for children to be learning through play and working hard.

Third, ‘learning is often unpleasant’. Well, who says so? I’ve not found it that way. Sure some aspects might be boring, even a chore, and there might not be any way round that, but I see no reason not to make the effort and to try to make learning as interesting and engaging as possible. Isn’t learning that captures the students’ interests, engages their concerns, and excites their imagination not better than learning that doesn’t? This seems a question that answers itself.

Fourth, ‘there is a danger of learning through play becoming trivial‘. This is a classic straw man argument. Of course, there is a danger learning through play might become trivial, just as there is a danger direct instruction might become deadly dull, but, and let’s be clear here, that is not the intention, and it merely takes an observant, contentious teacher to ensure that the learning remains the central concern of any activity and does not become another silly waste of student time. I’ve written more about this here – ‘Why Learning and having fun are not inimical’.

Now, I’m not pretending that learning through play is an easy option or even always the best method, there are clearly times when learning through direct instruction and/or other approaches are a better bet, just that it is an option and sometimes might be the best. Why would we as professionals not want to give ourselves the widest possible range of methods available? Sure, some might not suit our style, and some might take longer to learn than others, but why reason ourselves and others out of the possibility? This seems self-defeating.

However witty the prose.

The following is an extract from Chapter 5 of ‘A Beginner’s Guide to Mantle of the Expert’, I include it here as an example of how play can be used for learning, both at home and in the classroom.

“All play means something” Johan Huizinga

The full quote reads: “play is more than a mere physiological phenomenon or a psychological reflex. It goes beyond the confines of purely physical or purely biological activity. It is a significant function-that is to say, there is some sense to it. In play there is something “at play” which transcends the immediate needs of life and imparts meaning to the action. All play means something. If we call the active principle that makes up the essence of play, “instinct”, we explain nothing; if we call it “mind” or “will” we say too much. However we may regard it, the very fact that play has a meaning implies a non materialistic quality in the nature of the thing itself.” Huizinga, J. (1950) Homo Ludens: A study of the play element in culture. Boston: Beacon Press.

To illustrate the process I’m going to tell two stories. The first involves a young boy playing a game at home with his mother, centred on his own interests; the second involves a class of children in Early Years, working with their teacher to create an imaginary context, which they are using to explore the curriculum. Both stories involve the use of language and the way it moves the participants in and out of the fictional world.

Story 1: Imaginative play at home

A boy is watching his favourite film about dinosaurs, his arms and legs twitch in response to events on the screen, and his lips move as he repeats the familiar words of the actors. He knows the film off by heart and all around him are the dinosaur toys he plays with from morning to night: constantly lining them up in rows, organising them into sets, and bringing them together for epic battles. These things represent in their different forms (movies, toys, pictures, and stories) the landscape of his imagination, played out and repeated time and time again. Together, they provide for him a meaningful and exciting context to explore his ideas and to develop his personal understanding of the world. They are the bridges that link the internal world of his mind with the external world of reality around him.

When the film finishes, he jumps down from the sofa and lies flat on the ground bringing his eyes to the level of the dinosaurs. He looks at them intently for a while, exploring them from different angles, then starts to move them around, growling and roaring as they attack each other. Reaching into a box he pulls out a human shaped figure, dressed in kaki and carrying a rifle. He carefully places the figure behind a wooden building block and then edges him out so the figure can watch the dinosaurs without being seen. The boy then shifts his own position so he can lie behind the figure and see the dinosaurs fighting from a different point of view. In his mind, he has brought together his toys and the events of the film into a new landscape; an imaginary world where he is in control.

Suddenly, his concentration is broken by his mother calling him for lunch. Although he is reluctant to leave the world of his imagination, the boy notices his hunger and stops his game for food. The real world has intervened and for a while it takes precedence.

As he leaves his toys and walks into the dinning-room, the boy’s attention switches from the internal imaginary world of dinosaurs, to the external real world of home and family.

The two worlds continue to exist simultaneously for the boy for as long as he chooses or until his mind shifts onto something new. In a sense the dinosaur world of his imagination is nested within the real world of his home. During the time he is playing with his toys, the boy is foregrounding events in the imaginary world – dinosaurs fighting, explorers hiding – and pushing into the background the real world aspects of his home – the carpet, the sofa, the walls of the house. When his mum calls him for lunch, the emphasis switches and the boy concentrates instead on the real world events of sitting at the table and eating.

As they share lunch, the boy is keen to tell his mum all about events in his imaginary world. She listens carefully and asks him questions. Of course, she has heard much of it before, but she recognises it is important to her son and she is keen to encourage him.

“Tell me about this explorer,” she asks, “can the dinosaurs see him?”

“Not at the moment,” he replies.

“Are they going to?” she asks.

“Yes,” he nods.

“Then what will happen?”

“They are going to chase him,” he answers.

As they talk, the two of them are outside the fiction, in the real world, thinking about and discussing events in the dinosaur world of the boy’s imagination. Importantly, both treat this imaginary world as if it were real. The mother’s questions are serious and respectful, she does not want to diminish his game, while the boy’s answers treat her as someone he can trust. There is no sense of irony between them, she is not laughing at his earnestness or making sly comments that undermine his enthusiasm. She understands her son has invested a lot of his time and emotional energy in this world and for him it is a serious business.

After lunch the boy invites her to join in…

“Would you like to play?” he asks.

She checks the clock and agrees with a smile.

“You can be the T-Rex,” he says.

“Alright,” she replies, “show me how they look.”

The boy bears his teeth, turns his fingers into claws, and goes into a crouch. “AAAAAAAHHHHH,” he roars.

“I see,” says his mum, “so, how should we start?”

“You chase me,” he replies, “like in the film.”

“OK,” she says, letting out a roar of her own and chasing him into the lounge.

At that moment both mother and son have jumped into the imaginary world and the game begins. He takes on the role of an adult explorer, a resourceful character, unafraid, knowledgable, and able. His mum becomes a terrifying dinosaur with a mouth full of sharp teeth, hungry, intelligent, and intent on catching her prey. It is not that the real world has entirely disappeared – the furniture of the lounge is still there, the table in the dinning-room – it is just that the boy and his mother have chosen to push these things into the background of their minds, concentrating instead on the events, characters, and scenery of the fiction. This is a conscious and negotiated suspension of reality, agreed by both parties, in order to create a shared fictional world where they can enjoy being entirely different. The boy wants a safe and controlled way to experience the excitement of his favourite film and his mum is happy to help him by taking on the role of a T-Rex. Entering the fiction is easy for them, all they have to do is suspend their disbelief for a short time and play as if the imaginary world were real.

As they run around the lounge and up the stairs the T-Rex snaps its jaws and roars loudly, the explorer ducks and weaves trying to escape. Suddenly, the T-Rex grabs the explorer and (pretend) bites his neck, “AAAAAAHHHH!” It roars, chomping and biting.

This is too much for the boy and he bursts into tears. Without meaning to, his mum has gone too far, she has scared him and at that moment (for the boy at least) the story stops. His tears are real world tears, his fears are real world fears. His mum, recognising this change, stops being the T-Rex and turns her pretend bite into a cuddle.

The two of them are back now in the real world.

“I’m sorry,” she apologises, “I thought that’s what you wanted.”

“No,” the boy sniffs, “the T-Rex doesn’t catch the explorer.”

“Oh,” says his mum, “I got that wrong. Please, tell me what happens next.”

The boy explains how the T-Rex nearly catches the explorer, but misses, and how the explorer makes the dinosaur fall into a trap.

His mum listens carefully.

“I see,” she says, “I think I get it now.”

The boy stops crying and wipes away his tears.

“Shall we try again?” she asks, making her hands into dinosaur claws.

The boy smiles and agrees.

Turning away, he runs back into the jungle, dodging and weaving his way through the trees. His mum roars and chases after him. Now careful not to actually catch him.

Both are back in the imaginary world.

This is how child-initiated play works. The child decides on the fiction – location, characters, narrative – and the adult plays-along. To enter into the imaginary world of the child the adult needs to be invited in, she needs to ask questions to understand the context, and she needs to stop and start at the behest of the child. The child is in charge, it is his world, and the adult is entering the world on his terms. This is why when she gets it wrong, by grabbing him and making him cry, she has to come out of the fiction (stopping time in the fictional world) to apologise and renegotiate her way back in.

This process of stopping and starting the story so the participants can step in and out of the imaginary world is a fundamental aspect of imaginary play. It allows the participants to create and then re-shape the imaginary world as they want it to be. There is no final copy as such, just a temporary and contingent something, that those involved can enjoy for as long as they will.

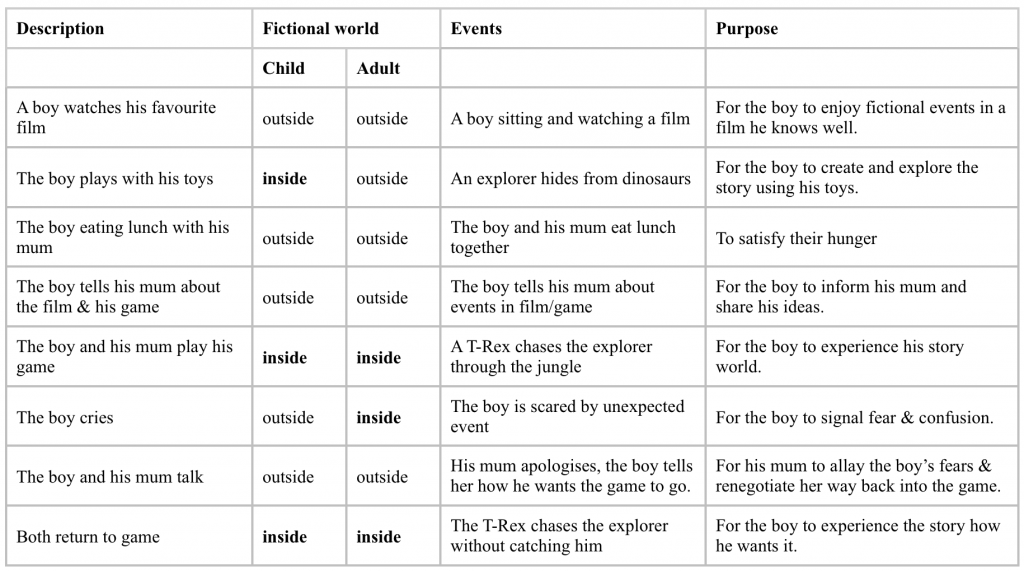

The following table illustrates the inside/outside/inside nature of the boy’s game:

It is important to emphasise the social and cultural dimensions of this process. The boy, although he is playing alone to begin with, is not inventing the world of his imagination from thin air. His game of dinosaurs, jungles, and explorers is a variation on what he has learnt from watching films, reading books, looking at pictures, and talking to others. When he involves his mother in this game she brings with her, her own social and cultural information about dinosaurs, jungles, and explorers, which, she can share and add to their combined pool of knowledge. For example, later, while they are building the trap together for the dinosaur (outside the fiction), she teaches her son how to tie pieces of wood together using string and tells him about other animals found in the jungle, such as tigers and pythons.

Imaginative play, then, is a medium for learning about the world (including its fictional dimensions). It creates psychological landscapes, where those participating, can connect new sources of information and experiences to existing banks of knowledge and understanding. This process is about making meaning, joining together, and forging links. It is also about exploring the use of power, taking risks in a safe environment, and expressing thoughts, ideas, and values. These represent the key aspects of imaginative play as a medium for learning.

They can all be found in the boy’s dinosaur game:

- It is a world the boy controls, that is operates under his rules. He decides what happens, when it happens, and who is involved. It is a place for him to explore what it is to have power and authority. Both, the opportunities and responsibilities.

- It is ‘safe zone’ the boy can use to generate exciting and risky scenarios. Ones that in the real world would be far too dangerous for him. Creating opportunities for him to explore risk and danger, their implications and opportunities.

- It is built from ‘stuff’ in the real world, that is story-lines, contexts, landscapes, creatures, and people. The boy can interact with these features and shape them for his own purposes.

- It creates a learning environment where the boy can make meaning of the world, that is experiment and explore what it is to be a human being, including the fictional worlds of his imagination.

- It is a landscape where the boy can make connections in his mind between what he knows and what he is finding out about, that is, the interactions between the two worlds can help the boy build cognitive bridges, connecting new and existing knowledge and understanding.

- It generates opportunities for the boy to create ‘products’, using various forms of representation – pictures, writing, enactive-movement, and spoken-words – for him to develop his skills of communication and human interaction.

As far as we can tell, imaginative play is something human beings do innately and universally from a young age. There is no need for the boy and his mother to go on a ‘How to Play’ course or to read books with titles like, ‘Play For Beginners’, they just know how to do it. And as the boy plays, he learns – just like other children have, from all over the world, for countless generations.

Story 2: Imaginative play in the classroom

The first important difference between imaginative play at home and imaginative play at school is that no one person is in charge of the imaginary world in the classroom. While playing at home, the boy is in charge of his imaginary world, he’s the boss, he decides what happens and when. In the classroom it is the community that decides, under the guidance and support of the teacher. Co-operation and compromise play a much larger role in school and the boy (along with his classmates) has to learn how to adapt and accept the different pressures and responsibilities this involves.

Unlike at home, where the primary focus of the boy’s imaginative play is his enjoyment, in the classroom the primary and over-riding concern is with curriculum learning. It is the teacher’s job to plan and guide the activities of the imaginary world in the direction of purposeful and productive learning. It is no good creating an imaginary world full of fun and excitement, where the children can’t wait to get into classroom, if nothing of any substance gets done and the activities are nothing more than a series of disconnected games, without curriculum purpose or direction. Such a place is not a classroom; it’s a playground.

Let’s imagine we drop in on the class about a week into their context called, Dinosaur Island. If we look around the room we can see signs of activity from the imaginary world on the walls of the classroom – health and safety posters, a map of the island, pictures of dinosaurs, lego-models of vehicles and buildings.

Currently, the children are sat in a circle on the carpet discussing with their teacher how to help an injured triceratops. Lying on the floor, in the middle of the circle, is a member of the class. She is curled up and still.

“Is she still breathing?” the teacher asks.

“Yes,” replies one of the children. Others nod in agreement.

“That wound looks nasty,” says the teacher, “did we bring a first aid kit?”

This first exchange is ‘inside’ the fiction. The child on the floor is representing the injured triceratops, the other children and the teacher are members of a team of explorers.

“Take a look in your rucksack,” says the teacher, opening an imaginary bag in front of her and modelling this way of working for the children.

They follow her lead.

“I think we’ll need one of these,” she says, holding up an imaginary syringe and squeezing it.

“What else do you think we will need?”

The children make suggestions.

The teacher supplements their knowledge with suggestions of her own. She is working in the moment, giving the class opportunities to make contributions of their own, but always looking to extend their thinking.

When they are ready, they set to work.

For the next fifteen minutes, the children (as explorers) operate as a team working together to save the life of the triceratops, while their teacher (taking on the role of a colleague) supports and guides their work. In this way, inside and outside the fiction, she is able to give advice, provide additional information, and direct activities.

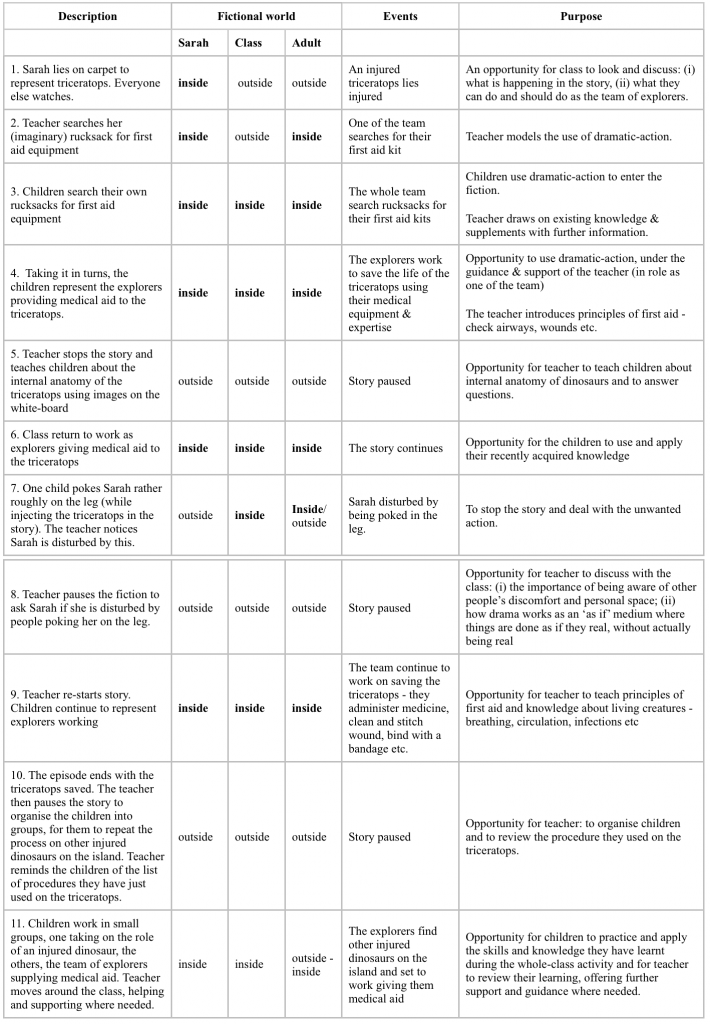

Occasionally, this involves her stopping the fiction entirely. She does this twice during the session. Once, to teach the children information on dinosaur anatomy (using a pre-prepared image on the white-board), and once to deal with one member of the Team who is administering his medicine rather too enthusiastically to the leg of the triceratops.

“We just need to stop the story for a moment.” She says, and then waits until everyone comes out of the fiction.

“Thank you. I’ve stopped the story so we can ask Sarah a question: Sarah, are you all right having people poke your leg while you are in the story?”

Sarah shakes her head.

“I thought not. We need to be more careful. Let’s try to remember we are working as if it were real, but Sarah doesn’t want people actually touching her. Shall we have another go?”

This exchange is very similar to the one between the mother and her son where they needed to come out of the fiction to discuss the T-Rex’s attack on the explorer. The process works in exactly the same way, even if the power dynamic is subtly different. In the home-based scenario, the mother plays the boy’s game under his rules and instructions. In the classroom, the teacher is the one in charge and has the power to stop and start the fiction when she needs to provide more information or deal with misunderstandings.

The purpose of the classroom activity is not primarily about having a good time (although the children might well be enjoying themselves), it is about learning, and so the teacher takes every opportunity she can to develop the children’s’ knowledge, skills, and understanding. She understands this involves regularly stopping and starting the fiction, but is not worried that this will wreck the imaginary scenario. As in imaginative play, she understands the children are quite capable of keeping both worlds in mind at the same time – the imaginary and the real.

Like the boy’s game, once the fiction begins it is not a simulated scenario that mimics reality and breaks down if it comes to a halt. Rather, it operates in a start/stop/start fashion, allowing all those involved the chance to come out of the fiction when they need to and to return to it when they are ready.

Of course, none of this works if the children are not interested in the world they are creating. Like play, you can’t make people enjoy it and you can’t force them to join in. They have to want to. This is why the teacher works hard at making the scenarios interesting and exciting for her class, and looks at every opportunity to include their ideas and suggestions. This is not a child-centred approach in the sense that the children make all the decisions and the teacher follows. Rather, it is a learning-centred approach that keeps the curriculum in mind, while always looking to include and involve the ideas, contributions, and interests of the children. It is a careful balancing act, tip too far one way and the work loses focus and direction, tip too far the other and the children lose interest and motivation.

Generating further curriculum learning activities

The imaginary context can be used to generate learning activities across the curriculum. To see how this happens, let’s return to the classroom.

The teacher is now standing in front of the white-board, with the students sat together on the carpet. She’s talking about instruction writing.

“I thought it would be helpful if we made a list of instructions for giving medical aid to the dinosaurs. They could go in our rucksacks, along with the first aid kits, and would be something we could give to new people when they join our team. What instructions do you think we should include?”

There is a short discussion, where the children and the teacher share their ideas.

“We are going to need to write these ideas down.” She says and writes on the whiteboard – Instructions for Giving Medical Aid to a Dinosaur.

“What do you think?”

There are some nods of agreement.

She continues and writes the number ‘1’ on the board, “How shall we start?”

For the next ten minutes or so the children and teacher work together to create a list of ten instructions. The teacher structures the work and helps with difficult spellings. As much as possible she wants to include the children’s ideas, but is mindful of what they don’t know. The list is a co-construction, not something the children have done alone and not something given to them by the teacher as a fait accompli.

Once they have finished the teacher introduces the next task:

“I guess we’ll all need a list of our own once we start going deeper into the jungle and further away from base. I’ve made a template, which you might find helpful.” She holds up a copy of the pre-prepared template. “There’s a space here for the heading, a box for a picture of a dinosaur, a place to put your own list of instructions, and another box for your equipment.”

The children set to work and the teacher makes her way around the classroom offering support and guidance where needed.

It might be interesting to ask the children as they work if they think they are in the real world or the imaginary world. But they probably wouldn’t care. The question has little relevance to their understanding of the context and would sound like the sort of thing adults worry about, but children rarely bother with – like Callum and his security dogs

For myself, I suspect they are in a kind of ‘shadow’ space between the two, where both worlds are held in their minds at the same time. With their imagination operating in the fictional space – with the dinosaurs and the explorers – and their concentration operating in the classroom space, focusing on the technical aspects of writing – spelling, punctuation, and grammar. This is the great asset of Mantle of the Expert it creates both the content and the reasons for studying the curriculum, making learning both enjoyable and purposeful.