What is the purpose of school?

I had been teaching for four years before I thought to ask my class what they thought was the purpose of school. The answers I got back where fairly predictable, “To get a good job when I’m older”; “To make more money”; “To learn more stuff”. These children were seven.

The reason I asked them was because I had noticed, unless they found an activity useful or enjoyable, many of them tended to lose concentration, and become distracted and disengaged. As a consequence, I seemed to be spending a great deal of my time trying to get them back on task.

This was both disconcerting and very hard work. A year can be a long time in a primary classroom, where you spend every hour of every school day with the same children, if these children are not self-motivated to learn.

My class were one of these and they drove me close to distraction. They were full of energy and enthusiasm, but would very quickly lose focus and were rarely prepared to listen or stick to a task once it became boring or difficult.

I had tried two well-worn strategies to solve this problem. The first was to plan activities I knew the children would like. This was fine in as much as when they were enjoying themselves they were much easier to manage, however, this strategy had the major drawback of not focusing the children on their learning. They were certainly having a good time, but they were not studying much.

The second strategy I used, was a system of punishments and rewards. I wrote a list of rules that went on the classroom wall, which I enforced rigorously, and a chart for recording stickers which I gave out for good work and good behaviour. This strategy kept the children in check, but it demanded very little effort from the students, other than compliance. The stickers soon lost meaning, as the children started focusing more on getting the stickers than on their own behaviour or their own learning.

These were short-term fixes that meant a lot of work for me and very little learning for the students. Keeping them going meant I had to be either a fun-time entertainer or a stern disciplinarian: An exhausting and generally ineffective juggling act.

It was about this time I decided to ask my class why they thought they were at school. As I have said already their answers were not particularly surprising, but they did make me think. They seemed to fall into one of two categories. In category one, they thought school was about preparing them for their future lives: “Learning will help me get a job when I leave school” or “Learning will help me make more money.” As motivations these seemed like very long-term goals for seven year olds.

I thought if I had to learn Japanese for a job I might be doing in ten years time, then practicing my Japanese pronunciation and developing my vocabulary would not be top of my current ‘to-do’ list. I would have more pressing concerns in the here-and-now: Such as spending time with my friends and family and studying subjects of more immediate use. There would be plenty of time (I would tell myself) to study Japanese later.

This, it occurred to me, was one of the problems I was experiencing with my class. They understood, well enough, that the work they were doing was important (or would be in the future), but it was not very urgent. They were finding it difficult to care much about doing things and learning stuff that might be useful one day in the indeterminate future, but not today.

The second category of answer, “Learning stuff”, was equally problematic because it was neither useful nor precise: ‘Stuff’ could mean anything. My students did not seem to have a vocabulary to talk about or understand what they doing in class or how they could get better at it. Again, they seemed to understand (in a vague way) that what they were doing was important, but not really so important that they could be bothered to care much about it now.

What the two categories of answer had in common was a lack of immediacy. The students saw school as a place where they practiced and learnt ‘stuff’ that might be useful in some imprecise way, at some indeterminate time in the future, but this future was so vague and distant they were not prepared to put much effort in to it in the here-and-now. This is why they wanted the lessons to be enjoyable, at least that way they could have a good time while they were doing the tasks.

Covey and urgent/important heuristic

I mulled over this problem for a while and tried various adaptations to my two main strategies. Nothing seemed to work very well, in the long term. And then I had a break-through, I read Stephen Covey’s book, The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People, and saw a table on time-management that seemed to suggest an answer to my problem.

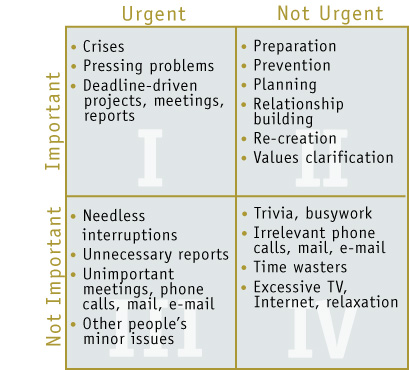

Covey’s table is a heuristic model for thinking about effective ways to manage time. It is divided into four sections:

The purpose of each section is to classify an activity depending on its urgency and importance. Unimportant activities should be avoided or minimised. Important activities should be prioritised and given more focus.

Furthermore, Covey argues, highly effective people manage their time so that they spend as much time as possible in the ‘important/not urgent’ quadrant, working on projects that will bear fruit in the long term. He maintains these people choose to do this because they are self-motivated, focused on the goals they want to achieve, and enjoy some control over how they will accomplish these aims.

As I looked at this table I began relating it to my own work and the work of my class. What I wanted was the children working consistently in quadrant 2 – focusing their efforts on long-term goals – but what I saw (more times than I was comfortable with) was the children getting bored or distracted and sliding into behaviour more associated with quadrant 4 – idle chat, frivolous activity etc.

I thought about Covey’s analysis and decided the reason for this slide was that the students did not find the work sufficiently meaningful and had not yet developed the necessary qualities, attitudes and dispositions of those people Covey called, ‘highly effective’:

- My students were not self-motivated towards learning

- They were not sufficiently focused on long-term goals

- And they had (or took) very little responsibility for the way these goals would be achieved.

Later, as I read around this subject, I learnt these problems were ones of agency, power/positioning, and intrinsic motivation. At the time I knew none of these terms, but I began to realise that the children in my class were not focused on learning, but on their own personal and social needs. Indeed, they were, if anything, learning-averse. Their attitude to learning was as something to avoid if possible, rather like an unpleasant chore that has to be done, but is best got over as quick as possible. If the learning was ‘fun’ they would go along with it for a while or if there was some kind of bribe – in the form of stickers, free-time etc. – but they were not disposed towards learning as something valuable or worth doing well or spending a moment too long on.

I concluded, this was why they were getting distracted and ‘messing about’ when they should have been learning.

I decided tackling this issue would become the main, long-term, focus of my lessons. I printed off a copy of Covey’s table and used it as tool for assessing the children’s engagement at different times and as a way of evaluating their disposition towards learning. I began making notes when I observed children sliding from quadrant 2 into quadrant 4, trying to spot what triggered this change.

After a while, it became apparent to me the intersection of ‘urgent and important’ in quadrant 1 had a different significance in the classroom, than the way Covey used it in his book. For Covey, an effective person would avoid quadrant 1 tasks (which they would view as time-consuming fire-fighting) by being organised and dealing with tasks before they became problems. Their aim would be to avoid tension and focus on long-term goals. However, in the classroom (where children are generally less self-motivated) the ‘important/urgent’ quadrant is not so much about time-management as creating activities that are purposeful and immediate. Demanding from the students a higher level of commitment and participation.

I realised I could create urgent/important problems (from quadrant 1) that would make learning activities more meaningful. Activities, that were not about preparing for some dim and distant future, but about dealing with problems in the here and now.

Here is an example:

Imagine planning a lesson for Year 1. The purpose of the lesson is for the students to practice writing warning signs, in order to prevent a terrible accident. Your aim is for them to learn some new vocabulary (stop, warning, danger, etc.), to use an exclamation mark, and to practice writing clearly and legibly.

The class are studying Traditional Tales. You choose to use the story of The Three Billy Goats Gruff.

Developing the context

- Read the story to the children

- After the story has ended, turn back to the start of the book where there is a page with the goats in a field.

- “I wonder if the Billy Goats knew the troll was under the bridge?”

- Have a discussion with the children where they share their ideas.

- “What if the story was slightly different and they didn’t know about the troll. What could we do to warn them?”

- Children share their ideas.

- “But what would happen if we weren’t there (we can’t be there all the time, we’re busy people) and some new goats came along? I wonder if we should put up some posters, warning anyone coming to the bridge, that there is a hungry troll underneath?”

Vocabulary, grammar and punctuation

- “I’ve got together some paper and pens we can use for this job.”

- “What sort of words do you think we will need?”

- Children make suggestions – write them down on a board, helping them with the spelling etc. Talk about making the words very clear, possibly using capitals and exclamation marks.

Co-construction

- Children work together, alone and/or with an adult to make the signs.

- Adults support and help.

- The children start sticking the signs up around the room in places where they think the goats will best see them.

Evaluation & Reflection

- An adult-in-role (AIR) as the a goat (not pretending to be a goat) and, possibly, a child-in-role as the Troll, sitting and watching.

- AIR comes in, looks around and sees the posters, she reads one out loud and then moves onto the next. We watch.

- AIR decides the bridge is too dangerous and moves away. The troll goes hungry.

- Talk to the students, “What did you notice?”

- “It looks as though the signs worked.”

- “What did we do that made them work so well?”

- “How did we do that?”

- “Did you see anyone today doing some work that impressed you?”

- “We must be the kind of people who…”

Further activity

- “I wonder if there are any other stories where we could use our signs to warn people?”

In this example the context makes the activity both urgent and important. This creates purpose, meaning and tension. The tension is something we feel because the activity needs to be done quickly and properly or it won’t work.

The purpose of the reflection at the end of the session is to focus the children not just on what was learnt specifically, but what the activity and the way they worked says about them as learners: Their shared knowledge, their skills, their qualities and their values.

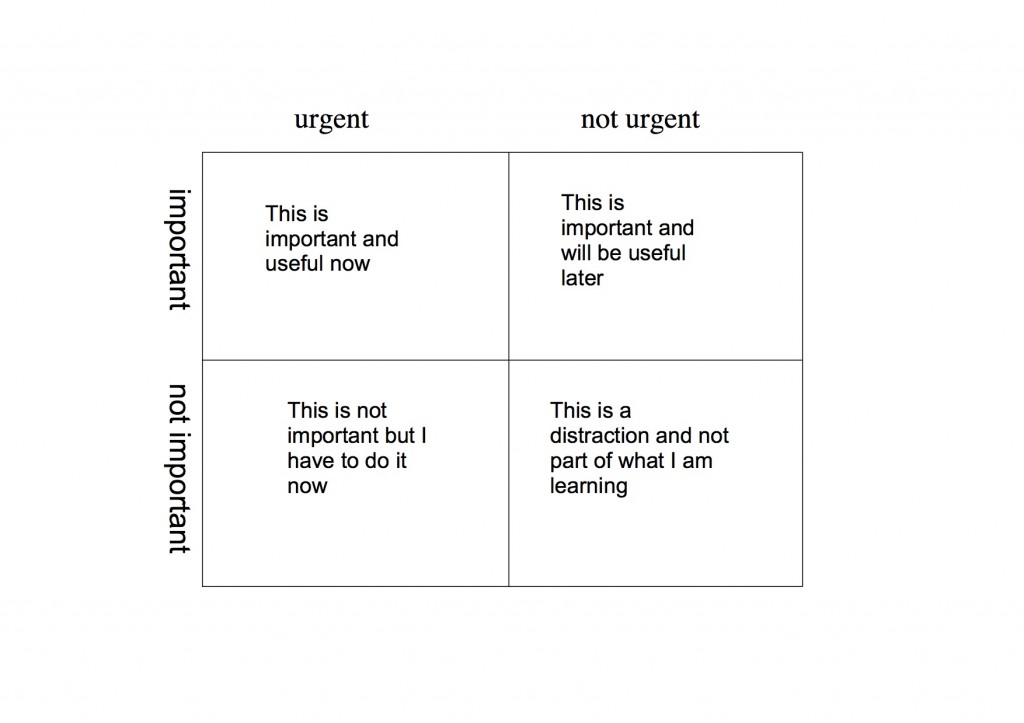

Working in this way can help the children to become more focused on the activity (and the learning they are developing) and less on themselves (their needs and personal interests). The urgent/important table can be used as a planning and lesson evaluation tool, but it is also a heuristic model for thinking about learning and where the children (as learners) are putting their energy and time. I now share it with my class and use it to help the students evaluate their own dispositions. If I spot someone slipping into quadrant 4 it is usually enough to remind them of the purpose of this time and what to focus on, “This is a learning time, that conversation is for the playground, do you need any help or can you manage this yourself?”

Reflecting in this way can help the students develop both a language for learning and a heuristic model for thinking about how they are spending their time and to what ends.

I now start every new year with the question, “Why are we here, what is the purpose of school?” This becomes the main inquiry question that focuses the children’s learning throughout the different subjects and curriculum areas they study. Shaping and changing the way learning happens in the classroom and how the students reflect on their own learning and the goals they set for themselves. As well as teaching all the knowledge I can, helping them acquire the skills they need and develop deep understanding of the themes we study, my overarching concern is to strengthen and develop the children’s attitudes and dispositions to learning. To think of themselves as learners, responsible and focused on their own development. In this way, I hope they will become experts in learning – not passengers on a train, marking time.

I use this adapted model of the ‘urgent/important’ heuristic with students:

I really enjoyed reading this Tim – thanks. I’m sharing it in the “Top Tips” part of Wednesday’s staff meeting; especially “This creates purpose, meaning and tension. The tension is something we feel because the activity needs to be done quickly and properly or it won’t work.”

Thank you Lisa, tension is an important, but often neglected, aspect of planning and teaching.

This really made me think and it seems an excellent way of motivating students to learn. So often we can forget that they need to understand the relevance of what they are being asked to do. When I started teaching in the 60’s no one cared about motivation, children were ‘encouraged’ to work and stay on task by strict discipline. This seems to me a much better way to educate.

Thank you Tony. Ideas on ‘motivating’ students have certainly moved on since the 60s, but I think there is still someway to go. Strict discipline, as a strategy, seems to be having something of a revival at the moment, although (as I argue in the blog) I’m not convinced it is a very effective approach long-term.

Thanks Tim, this made really interesting reading and really made me think about the way in which I want the children in my class to think about their learning.

Thank you Sarah, I’m glad it is helpful. It was certainly a ‘breakthrough’ moment for me.

I shared your grid with the children today Tim. Interesting discussion about a making a map of an island – they said that yesterday it was important for our story but not urgent. But that today it changed to be important and urgent as we weren’t satisfied with the outcome from the day before. Great!