Last week I wrote a blog about obedience. I think it is fair to say it had a mixed response. However, I did have some very interesting conversations on Twitter and there were some very thoughtful comments under the line, so I’ve decided to write a follow up.

I’d like to explore in more detail the range (as I see it) of different strategies we can draw on as teachers beyond merely getting the students to obey.

Some might say – “Why bother? Kids should just do what they are told, no questions, then we can get on with the job of teaching them.”

I’d consider this a very low expectation. The very minimum we can ask of our students is to come into a room with their mouths shut, sit where they are told, and do what’s required.

Of course, for some students even these simple rules offer a massive challenge, both to their own status and to their relationship with authority.

How we integrate these young people into the school community is a massive problem (at last count there were over 5,100 children permanently excluded from education. Where are they? What are they doing?).

A common answer is, make them obey. But this seems a dead-end to me.

Are we looking to turn our schools into boot camps, with ever stricter rules and harsher punishments? Where does it stop? If we exclude those that refuse to obey, where do they go? And how do they go? What have they learnt about authority and the unbending, no compromising, power of adults? What do they do next?

As I say, it’s a massive problem and I’m not down-playing the challenge of having non-compliant students in your classroom, I’ve had plenty in my time. Head-bangers my dad calls them.

But, what is the answer? Pandering to their whims doesn’t work, neither does forcing them to obey.

We might not like it, but doing the same old things and hoping for different outcomes, is not clever.

We need to start searching for new answers to these problems. Dichotomising the argument, sneering and ridiculing (which I see often on Twitter), and dismissing the ideas of those who want to think beyond the stale old strategies, is not helping.

Happily, there are many in the edBlog/edTwitter community who are prepared to think differently and to strive to raise the debate above a battle between competing sides.

This blog is for them.

Power and Positioning

As with many things in education, Dorothy Heathcote was ahead of her time with her thinking on how power and authority should be used in the classroom.

She talked about power being something teachers hold on behalf of their students. Not over them, like a threat, but in their interests, for as long as they need it. She was not afraid to be authoritarian, learning was always the most important thing for her, but she was always looking to share her authority, and the responsibilities that came with it. She understood we can’t just thrust responsibility onto children and expect them to bear it. The transfer needs to be planned, staged, and mediated. It is a delicate process – too much responsibility, too early and the children will fail; too little responsibility, too slowly and they will learn to rely on the adults to make all the decisions.

Heathcote proposed another way of thinking about power and authority in the classroom. One that recognised the importance of control (both teacher control and the students’ self-control), but also stressed the importance of creating opportunities for students to experience, explore, and develop their own power, authority, and responsibilities. This she called positioning – the teacher positions her own power in relationship to the students’, always asking: “What do these people need now to help them learn?”

Brian Edmiston discusses this in more detail in his essays, ‘What’s My Position?’ and ‘Building Social Justice Communities’. Basically, he suggests there are three positions the teacher can take in relationship to their class: ‘Power-over’, ‘Power-with’ and ‘Power-for’.

In the power-over position the teacher holds all the authority. The children are merely required to comply. In power-with the teacher positions herself as an equal partner in the use of authority, working collaboratively with the class to make decisions. In power-for the teacher gives the authority temporarily to the children and follows their lead.

Each of these positions is a strategic move, used by the teacher, to develop the children’s learning and their experience of using power and having responsibility.

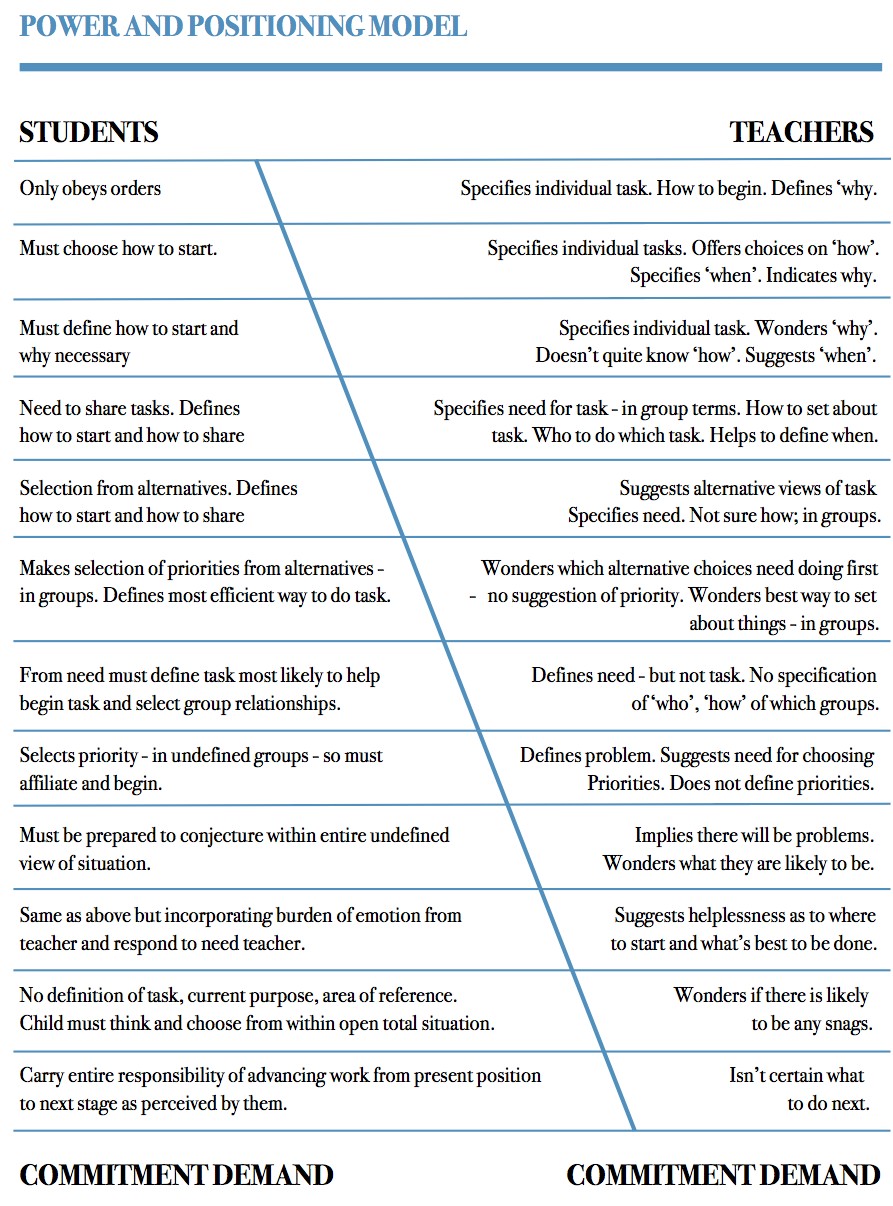

Heathcote summarised her thinking in this table.

At the top the teacher has power-over the children: the teacher makes all the decisions, the children obey.

As we move down the power begins to shift towards the students. By halfway the positioning is power-with, with the teacher sharing the decision-making process with the class.

The power continues to shift as we move further down. By the bottom of the table the power is decisively with the students. Strategically the teacher has put them in charge, now they are the ones making the decisions and the teacher is uncertain what to do next.

It would be a mistake to think this is an ethical transference of power from the adult to the children, so the children can take control. It is strategic and temporary, planned and mediated by the teacher to facilitate learning. In fact, during a session the teacher is likely to move both down and up the table, positioning themselves in relation to the class and renegotiating how power is being used as the learning develops.

Of course, Heathcote was primarily interested in using imaginary contexts for learning. It is important to remember much of the experimental use of power for the children is happening in imaginary situations where people are protected if things go wrong. A good example of this transfer of decision-making happens in the Mountain Rescue context on the planning page. In this scenario there are two adults working with the class, one as a member of the team, sharing power collaboratively, (power-with); the other representing an injured climber desperately in need of the children/team’s help (power-for).

Without pretending this kind of power-positioning is either easy or straight-forward, I would argue Heathcote’s table is a fantastic resource for thinking about how power and authority can be manipulated in the classroom: and then used to generate meaningful learning opportunities to help students experiment with power and develop their own understanding about collaboration and responsibility.