You may have noticed there is a narrative argument currently popular among some education commentators that lays the blame for all our educational ills at the door of the progressive movement.

This argument makes the claim that the progressive movement is built on a central principle, originating from the French philosopher Rousseau, that children are natural learners who learn best when they are left alone to discover things for themselves. This is a mistake, they say, which has distorted and corrupted our system of education in the 20th century and resulted in a facile curriculum and ineffective teaching methods.

Progressivism has become so deeply embedded in the system, the argument continues, educators and curriculum designers are not even aware of its malign influence on their thinking. It has even permeated the very language of educational discourse, making it almost impossible to stand outside the system and analyse it dispassionately.

It is a beguiling narrative because it allows us to blame the educators of the past for our current ills and gives us the chance to wipe the slate clean and start again. Much of our beloved secretary of state’s pronouncements have used this argument allowing him to justify his neo-liberal reforms as the sweeping away of the evils of trendy teaching that have infected our schools since the 1960s. Apparently freeing schools from the corrupting influence of progressivists in the local authorities and universities will allow them flourish and grow again. A bit like a garden after it has been weeded.

Leaving aside for the moment whether the ‘blame the progressives’ argument has any merit (I plan to write about this soon), being labelled as a progressivist in such a highly charged and hostile environment – you’re either right or you’re wrong’ – is not a comfortable state of affairs. Who wants to be considered a weed?

It is, therefore, I would suggest, important to be clear about what we mean by progressivism and what it is to be a progressivist. Since being on the wrong side of the argument runs the risk of being an apologist for everything that is, and has even been, wrong with the system.

The rest of this blog, then, is an attempt to uncover the fundamental principles that underpin progressivism: that is the ideas, values, and theories that make it a distinct ideology. Readers can then examine their own ideas, values, and theories against this list and decide for themselves if they are what might called, a progressivist.

First, some history…

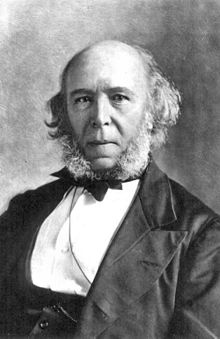

Herbert Spencer

Kieran Egan, an educational philosopher at Simon Fraser University, has written extensively on the subject of progressivism. In his 2002 book, ‘Getting it Wrong from the Beginning’ he argues the true founding father of progressivism is the Victorian philosopher, Herbert Spencer.

Now, little remembered, Spencer was a super star in his day, feted and honoured in both Britain and the USA, and sold over a million books in the last half of the nineteenth century.

Now, little remembered, Spencer was a super star in his day, feted and honoured in both Britain and the USA, and sold over a million books in the last half of the nineteenth century.

Although influenced indirectly by Rousseau (he never actually read ‘Emile’ because he was horrified by socialism and all its associated ideas [p.24]), Spencer was most influenced by the scientific discoveries of the nineteenth century that proved everything in the universe is in not fixed, as once believed, but in a constant state of change or, as he saw it, progress.

Spencer took this discovery and made a universal theory of it, which included educating the young.

As Egan writes, “Spencer proposed we live in a dramatic universe that is subject to constant change and this change follows developmentally from the simple to the complex. We can see the same laws operating in the cosmos at large, in the evolution of species, in the development of societies in history, and in the changes from the child is to the adult’s mind.” [p.15]

This idea of universal progress (progressivism) took hold and was expanded in the twentieth century by educationalists, such as Dewey and Piaget, and became the dominant ideology for thinking about and planning for education in Britain and the USA, even by people who had never heard of Herbert Spencer.

The principles of progressivism

The central tenet of Spencer’s pedagogy is the claim that children’s understanding can only expand from things they have direct experience of. Therefore, educators should always start from what the child already knows and progress from there. This is a natural process, Spencer argues, because children are naturally inquiring, constructing, and active beings. “We must constantly conform to the natural process of mental evolution. We develop in a certain sequence and we require a certain kind of knowledge at each stage.” [p.17]

From this starting place Spencer laid out seven principles for intellectual development:

1. We should proceed from the simple to the complex.

2. Development of the mind, as all other development, is an advance from the indefinite to the definite.

3. Our lessons ought to start from the concrete and end in the abstract.

4. The education of the child must accord, both in mode and arrangement, with the education of mankind, considered historically.

5. In each branch of instruction we should proceed from the empirical to the rational.

6. In education, the process of self-development should be encouraged to the utmost. Therefore, children should be led to make their own investigations, and to draw their own inferences. They should be told as little as possible, and induced to discover as much as possible.

7. Students should find the experience of learning pleasurable. [pp. 17–20]

Decide for yourself

I don’t have the time to go into each of these principles in detail – if you are interested then I recommend Egan’s book, it is both erudite and accessible – but these bare bones should be enough for readers to use as a checklist against their own principles and to decide if they correspond enough to justify the label, progressivist.

For my part, I don’t think it is enough to call someone a progressivist just because they are not convinced by the values and methods of traditional education. Neither, is it justified to call someone a progressivist just because they desire similar outcomes to those who are happy to carry the label. Rather, I would argue, progressivism is a distinct ideology (as outlined in the seven principles above), which either you adhere to or you don’t. If you read through the list and find yourself agreeing with most, if not all, of Spencer’s principles then I would say you’re a progressivist. If, on the other hand, you read through the list and you find yourself disagreeing more than agreeing, then I would say you’re not.

For my part, I don’t think it is enough to call someone a progressivist just because they are not convinced by the values and methods of traditional education. Neither, is it justified to call someone a progressivist just because they desire similar outcomes to those who are happy to carry the label. Rather, I would argue, progressivism is a distinct ideology (as outlined in the seven principles above), which either you adhere to or you don’t. If you read through the list and find yourself agreeing with most, if not all, of Spencer’s principles then I would say you’re a progressivist. If, on the other hand, you read through the list and you find yourself disagreeing more than agreeing, then I would say you’re not.

And don’t let people tell you otherwise.